Bridging: Journalism and Advancement

Supporting development without compromising our ethics.

By Dale Keiger

In May 2013, Johns Hopkins University announced a new and massive effort to raise $4.5 billion. The campaign would be called Rising to the Challenge. Those of us on the editorial staff of Johns Hopkins Magazine heard about these big plans and thought uh-oh.

As experienced university magazine editors, we knew that senior administration and development would be enthusiastic about a major campaign story in the magazine. As experienced publishing professionals, we knew that what they had in mind was a bad idea.

The audience for campaign stories, especially long ones in the feature well, is vanishingly small. According to the 2013 CASE Member Magazine Readership Survey, alumni readers’ interest in institutional affairs ranked second-to-last, and among institutional affairs stories, “fundraising” ranked eighth out of 10. (And number 10, the least interesting? Donor profiles.) Johns Hopkins Magazine’s own survey in 2008 had found that interest in “status of capital campaign/profiles of donors” ranked dead last. We did not want to lose four or six pages of valuable magazine real estate to a story that we believed everyone would ignore. But how to convince the bosses?

When I started at Johns Hopkins 26 years ago, many university magazines, including ours, were published by news and information departments. Now, almost all of them come out of communications departments. That is an important but rarely noted distinction. Many of us used to report to former journalists who had signed on with universities for better hours, better pay, better benefits, and more stable employment. They knew how to engage readers because they had done it for a living. Now we report to institutional communications professionals, and they look at our magazines from a different perspective. They — and, I believe, the vast majority of senior administrators — cast an eye on the magazine and think, Okay, how do we best use this platform to tell the alumni what we need to tell them?

A reasonable question, but it collides with what editors know: We can’t tell our readers anything. We cannot dictate what we think should be of interest to them. We can only approach them with some well-crafted stories and do our best to wrest their attention from the newspaper, The New Yorker, the phone, and the remote. We cannot do that by expending 3,000 words on a six-page campaign spread in the magazine, because our readers have told us that they just don’t care. Sure, a few really, really rich alumni care, but the other 99.8 percent of the magazine’s readership does not, not enough to read the kind of story administration wants. Many of our readers are willing to write checks, and bless them, they do. But not because a hackneyed campaign story ran in the magazine.

At Hopkins Magazine in 2013, we knew all of this. We were magazine pros, good at our work, with decades of experience at grabbing readers and holding on to them. We decided our best strategy for avoiding campaign coverage that wouldn’t work would be to proactively look for the sort of stories people actually read, good stories that might be lurking in the plans for adding $4.5 billion to the university’s coffers.

The first thing we did was read the university’s description of Rising to the Challenge. Some very smart people had thought this through and organized the campaign around three “pillars”: advancing discovery and creativity, enriching the student experience, and solving global problems as one unified university. (Hopkins has 10 divisions that historically have gone much their own way.) There would be five “signature initiatives”: the science of learning, a vast effort for global clean water, individualized health care, something not yet well-defined called the Global Health Initiative, and an effort to revitalize American cities.

If your mind started to wander near the end of that paragraph packed with campaign information, you see why we did not want to run six pages detailing and touting the campaign. What could we offer to our bosses as better ideas?

We seized on the signature initiatives. The campaign was to be a four-year effort — though it turned out they had been raising money during a three-year “quiet phase” and already brought in $1.9 billion — and we hit on the idea of taking each signature initiative and finding a good feature story nestled inside it. These would not be campaign stories, per se, but science or medicine or policy stories that stood on their own as features and just happened to mention, in a paragraph or two, that this work would be supported by Rising to the Challenge.

We saw several advantages to this approach. Of course, we avoided the deadly announcement piece that all would ignore. In defending that decision, we could point out that we were now planning not one story, but five features over the next four years, all legitimate, albeit somewhat disguised, campaign pieces. More to the point, we would be writing stories that kept our readers engaged with the institution and its superb work. There are always those at a university who want the alumni magazine to be a development tool. We needed to protect the magazine from that thinking. Not because we opposed development or the campaign; our employment depended, to some extent, on the campaign succeeding. But we knew two things. One, readers who give money to the school are readers who still feel part of something worthy. Two, those generous readers have to remember what makes the institution worthy, because nobody writes a check the minute they finish a magazine story or hear of a new campaign. They write that check later, when they remember how much the university means to them. And everything I’ve learned in 40 years of magazine work is that people do not remember articles chockablock with details about a new campaign. But they remember stories that engaged their hearts and minds and made them feel part of something that matters.

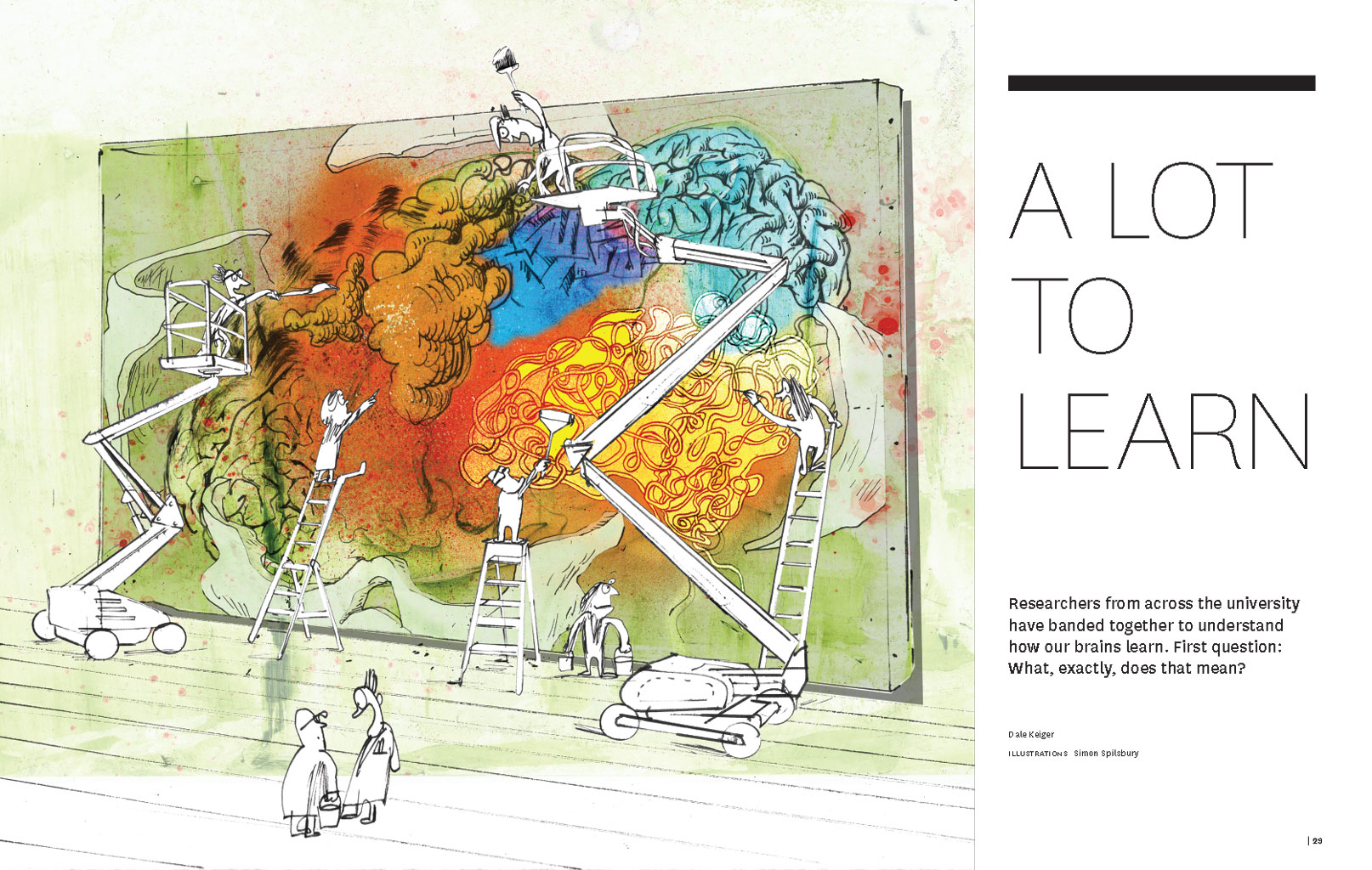

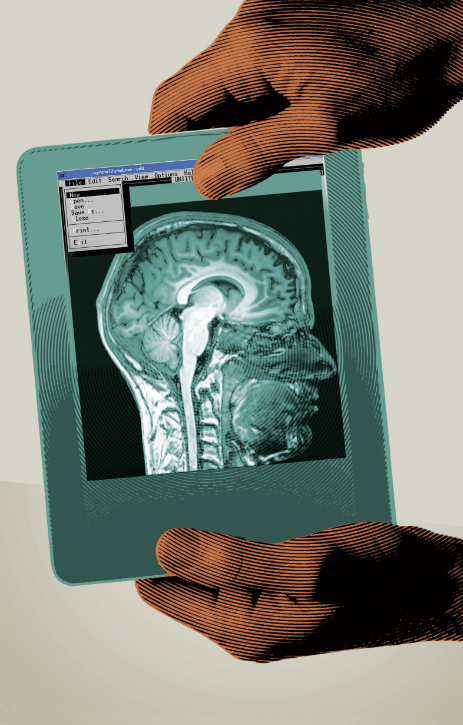

At the time, I was associate editor and the staff’s biggest science nerd, so I stepped up first to look into the science of learning. I soon realized there were a number of fascinating Johns Hopkins scientists across several disciplines who were eager to talk to me about their work and who all agreed on a fundamental problem: Neuroscience knows an awful lot about the brain, but doesn’t know beans about how the brain learns. Oh, yeah — I had my story.

I led with a neurologist: “Barry Gordon is a voluble man on the subject of the human brain. There is a volubility even in the inventory of his professional disciplines: neurology, cognitive neuroscience, neuropsychology, behavioral neurology, experimental psychology. … Ask him about the brain, which he has been studying at Johns Hopkins since the 1970s, and he can riff for 20 minutes about what is known and how much is not known, and the oddities of memory and the conservation of brain biochemistry across eons of evolution and questions that no one can answer despite centuries of pondering.”

In the second graph, I slipped this in: “Late in 2011, Gordon was brought into a small network of people who for a few years had been discussing the ways and means of supporting and expanding mind/brain science at Johns Hopkins. The ways part of the conversation centered on acknowledging that while Hopkins was strong across several disciplines — cognitive science, neuroscience, neurology, psychology, and more — those disciplines did not interact as well as they might. The means part concerned the ‘Rising to the Challenge’ fundraising campaign, which had begun its quiet phase in January 2010 and was to be publicly launched in 2013.” Just like that, my science feature became something we could point to as a campaign story. That was the only mention of the campaign in the entire piece, but that still worked for the campaign because over six pages it pulled readers into the kind of fascinating, essential work Hopkins scientists were doing, work that would be funded by Rising to the Challenge.

One signature initiative down, four to go.

That first story appeared in September 2013, and it was no accident that we moved fast to get a campaign feature into the magazine — we wanted a piece that would demonstrate to development our ambitious plans to publicize the campaign, and show that we appreciated the urgency of the task by pulling together a big story barely four months after the campaign announcement. We got no complaints. (Well, one: We now had another Johns Hopkins neuroscience institute that wanted to know when their feature would appear in the magazine. I wrote that one, too.)

Nine months later, we ticked the second box with “Water, water, everywhere?”, another six-page story about a second initiative, this one pertaining to global water sufficiency. Written by Michael Anft, it began: “Consider, just this once, that droplet of water forming on the lip of your kitchen faucet. Its story is likely richer than yours, and infinitely longer: It dates back at least 4.5 billion years to when the earth was formed. It came from outer space, where the molecules that make water possible were formed in the Orion Complex, part of the Milky Way. And during its earthly existence, that one seemingly inconsequential drop has gotten around — embedding itself in clouds, drifting through oceans, alighting on flower petals, and sloshing around in the bladders of brachiosauruses — before making itself of service to you (or, more likely, before coursing its way down your sink’s drain).”

I submit that many, many people read that lead and kept going, unaware they were reading a campaign story. Mention of Rising to the Challenge does not appear until the eighth paragraph, and as in the first story, that’s the only reference to it.

In Spring 2015, we wrote another initiative piece, this one on individualized health: a campaign story disguised as a deep dive into how computational science and biostatistics were enabling a level of individualized health care never imagined until a few years ago. Then a funny thing happened. No one in development ever really defined the fourth initiative, global public health, in a way that pointed us toward a story, so we didn’t write one. I suspect no one noticed. Nor did we do a story on revitalizing cities because for various reasons the campaign ended up deemphasizing that one.

In the end, we dodged the deadly, avoid-at-all-costs, 3,000-word campaign announcement and satisfied everyone with three features that I was more than happy to see in the magazine. And there is one more thing worth covering here. Our strategy derived from my belief, confirmed by experience, that the best way to ease your boss off of a bad idea is to approach the conversation like improvisational theater. The first rule of improv is “always say ‘yes’ to the scene.” What this means is when another actor sets the scene, you do not say no, you do not change it to something else. You go with it, adding something that swerves it just a little. The next time your vice president comes to you with a bad idea, you’re not likely to get very far if you just say no. My response instead was always, “Sure, yes, I can see that. But … I wonder if this idea might be better? What do you think?” The beauty is I was never overtly butting heads with senior management. I was positioning myself as a team player who added value to the boss’ idea; all the while, I was doing my best to turn a bad suggestion into something that would work for the magazine and its readers.

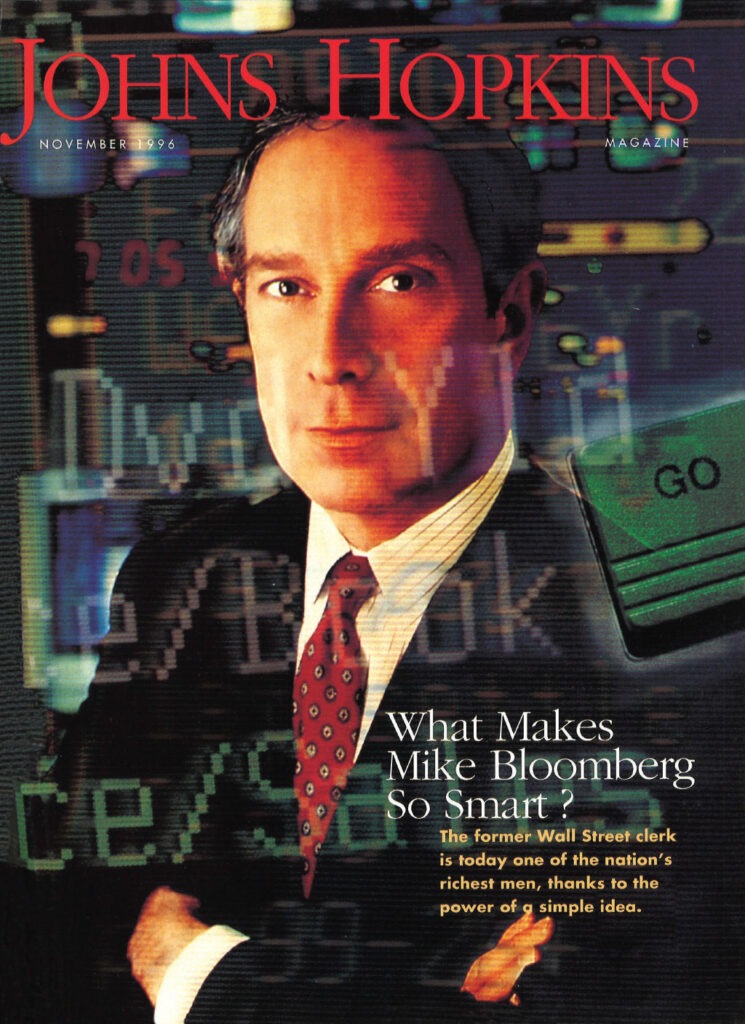

One more example. Michael Bloomberg, billionaire and former mayor of New York (and now, former presidential candidate), has given Johns Hopkins more than $1 billion over the years and recently pledged another $1.8 billion. His first major gift came in 1996, a pledge of $55 million, at the time the biggest ever to the university. Of course, eyes turned to the magazine in expectation of a donor profile, which, as I’ve already pointed out, every reader survey demonstrates is a story that nobody reads. Ever.

What to do? Bloomberg was a striking business success, and I was a former business reporter. So, I wrote a business feature on how Bloomberg built his company, a story that would not have been out of place in Forbes. A substantial number of our alumni are entrepreneurs or corporate executives, so we figured we could attract them to the piece, and maybe others who just like a good success story. We did not sing Bloomberg’s praises; instead, I wrote a narrative about how a clever, determined man turned himself from a finance guy with no employer and no clients into a billionaire. Along the lines of our Rising to the Challenge stories, there was only one mention of Bloomberg’s gift, the only hint that this was a stealth donor profile: “If you accept Forbes magazine’s estimate — Bloomberg does when it suits him — he’s personally worth $1 billion. To Hopkins, of course, he’s the new chairman of the Board of Trustees and the $55 million man — donor, in 1995, of a gift so big one faculty member quipped that the university might soon rechristen itself if Bloomberg agrees to add an ‘s’ to his first name.” We even got away with a cheeky headline: “What Makes Mike Bloomberg So Smart?”

I come back to our central conundrum as editors: We are publishing professionals who work for communications professionals. We sometimes — all too often, at least once per issue — have to take a bad, or at least not very good, idea and spin it into a story that at the least does not do damage to our magazine, and sometimes points us toward good stories we might not otherwise have published. You will never win every argument over the contents of your magazine. You may be lucky to win one out of every four. But with a little savvy improv, you can still make a magazine that your audience will read. And that, right there, is Editor’s Job One.

Dale Keiger is the retired editor of Johns Hopkins Magazine. He now works as an essayist and photographer, when he’s not driving his wife, a health policy consultant, around the country. Connect via keiger@pagesthemagazine.com.