By Dr. Joe Webb

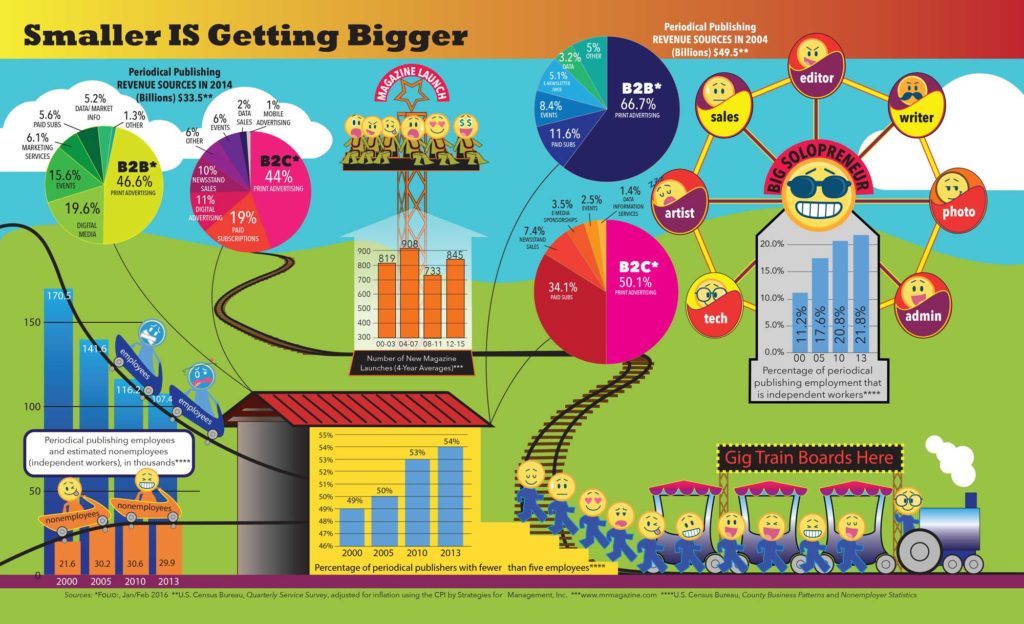

See full infographic below.

Publishing in North America wasn’t always populated by mega-enterprises. In fact, the industry started as a collection of small entrepreneurial businesses, with larger publishers taking shape and achieving financial and visible prominence only after World War II. That is changing. After a 50-year pattern of ever-larger publishing ventures, the data now show a return to smaller enterprises. Armed with new technologies in a hyper-connected marketplace, small publishers, and even sole practitioner publishers, are growing and thriving.

One of the indicators of this trend lies in magazine publishing employment. The U.S. Census Bureau’s County Business Patterns annual reports show that industry employment in 2000 was 170,500. By 2015, it fell to 98,500 — a level last seen in the late 1980s. Everyone in the industry has felt or witnessed the pain. Large publishers, primarily, closed their doors and shed significant numbers of workers. In 2000, there were 92 publishing companies with 250 or more employees; by 2014, there were 48.

The question is, where have these employees gone? Did they migrate to different industries? Or, perhaps, have they moved to different corners of the same industry, changing its fundamental structure?

When we dig further into the data, we see areas of growth — all of them consolidated in the arena of small publishing. We see an increase in the percentage of publishing companies with fewer than five employees. Since 2005, more than half of all periodical publishers (now 54 percent of them) have a staff this small. If we stretch the lens back further, we see that these publishers have more than doubled in number since 1986.

There is also growth among companies with just one employee, or “sole practitioners.” In 2000, there were 21,600 such businesses. By 2013, their ranks increased by 38 percent to 29,900 companies.

Technology has enabled this substantial shift. Advances in page-creation software, digital-image processing, and networking have stimulated an expanding base of freelance writers and editors, photographers, graphic designers, and advertising representatives. So it is now possible for one business owner to connect with all of the necessary resources to publish in print and online. And these smaller businesses have a flexibility and scalability that was not possible decades before. It’s a fundamental departure from the mega-enterprise business model where every necessary skill, capability, and resource resided within the enterprise itself.

As a group, these freelancers surface as a growth point in the data. They are “nonemployers” in labor statistics jargon because they work for and by themselves. And in this case, they are freelance publishing experts, involved in sales, production, editorial direction, and other tasks, selling their services to publishers or becoming small publishers themselves. In 2000, 11.2 percent of periodical publishing employees were independent workers; by 2013, they were 21.8 percent — nearly double the number in a dozen years.

What we see emerging is a “gig economy.” Publishing is quickly adopting the Hollywood Studio model wherein a variety of highly skilled people are assembled for a particular project, work intensely on it for a limited period of time, and then disband to move to the next project. In many cases, they work together in serial fashion, but not constantly. The groups often change from project to project.

“Displaced” publishing employees from larger enterprises have also moved to advertising agencies and public relations thanks to the “content marketing” revolution. Employment in public relations agencies is now 56,000, up by a thousand employees a year since 2003 — and this isn’t because companies are producing more press releases. These agencies have publishing professionals creating branded content from advertorials to social media campaigns to print publications. Add sole practitioners to these numbers, and the annual employment increase is doubled. Today’s total employment in this arena is about 90,000, almost as large as magazine publishing itself.

Where else is publishing employment growing? The U.S. Census Bureau initiated coverage of a new industry category in 2008: “Internet publishing and broadcasting and Web search portals,” a title only statisticians could love. In 2014, the category already had more than 4,800 establishments with fewer than five employees, plus 44,000 freelance workers. Keep in mind that the Census Bureau numbers cannot convey whether these enterprises are digital pure plays. It categorizes based on the largest aspect of revenue at the time of the data collection, and we know that’s more dynamic than ever. How would you describe your own publishing enterprise if you’re media agnostic, producing print, digital, video, and audio content?

Looking at the big picture, here’s what the data are telling us about the publishing industry:

- Publishing as an activity is thriving, despite all of the doomsayers. New magazines (granted, with fewer pages and less frequency) continue to appear at a pace of about two a day, unabated.

- Entrepreneurial small and solo publishers are agile enough to defy categorization and easy tracking. And, they find audiences that defy categorization as well, detecting and serving readers that larger publishers can’t or won’t.

- Between the data points, a robust, media-agnostic cadre of small, versatile publishers appears to be growing and thriving. There is no shortage of content and creativity.

The current state of publishing and the trends that led us here are depicted in the infographic below. We’re interested in your feedback. Do your experience and your business appear in this snapshot? And if not, how are they different? Tell us at the Lane Press Publishers’ Network on LinkedIn: tinyurl.com/linkedin-publishers-network.

Dr. Joe Webb is a 35+-year veteran of the graphic arts industry and is one of its best-known consultants, forecasters, and commentators. His “Mondays with Dr. Joe” column is a must-read feature at WhatTheyThink, where he also directs their Economics and Research Center. He founded the market research service TrendWatch Graphic Arts in 1994, which was sold to Reed Elsevier in 2000. He is a Ph.D. graduate of NYU’s Center for Graphic Communications Management and Technology. “Dr. Joe” is co-author with Richard Romano of several books, including Renewing the Printing Industry, Disrupting the Future, Getting Business, and This Point Forward.

Connect at tinyurl.com/linkedin-webb.

Data source: U.S. Census Bureau, County Business Patterns and Nonemployer Statistics.